Kerry James Marshall’s “The Histories”: A Bold Retelling of African and Black Experiences

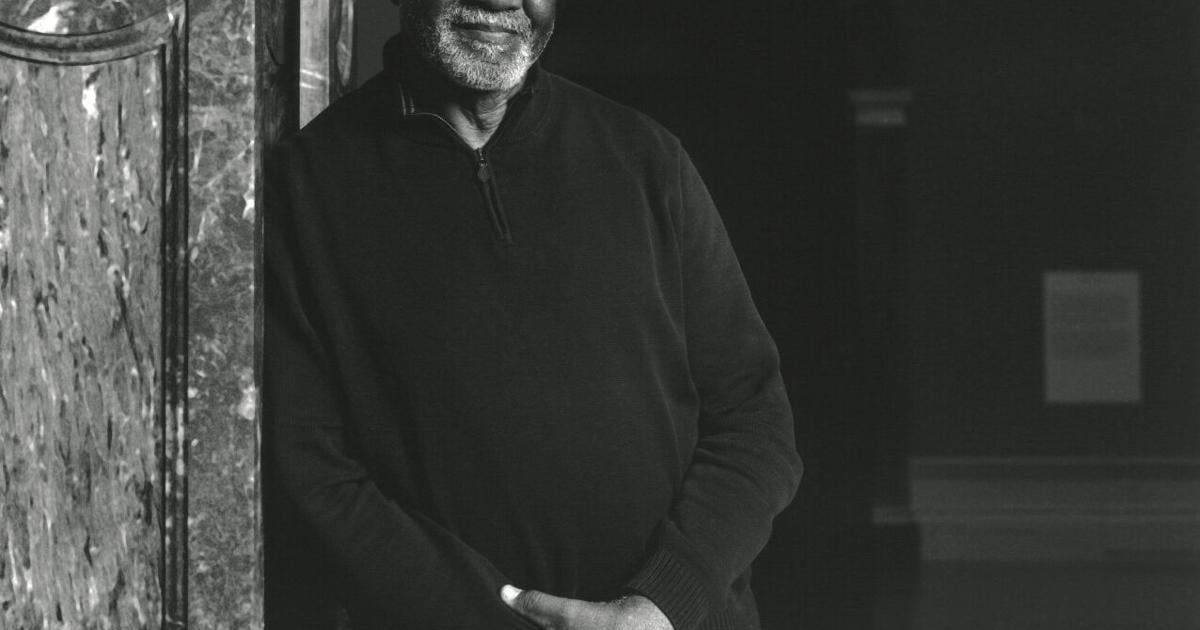

LONDON — The day before his survey exhibition “The Histories” opened to the public — his largest presentation of work in Europe, featuring more than 70 works created over four and a half decades — Kerry James Marshall sat in one of the soaring picture galleries of the Royal Academy of Art.

On the walls hung his newest paintings from the series Africa Revisited, several of which focus on the significant role African elites played in capturing and selling other Africans to European slave traders. This subject has been widely documented by historians but rarely, if ever, addressed in visual arts.

After days of showing collectors and VIPs through the exhibition — “doing the necessaries,” as he put it — Marshall, 69, was feeling good. “This body of work really represents a high-water mark,” he said. “I’m pouring everything — the accumulated knowledge, the ability, all of that stuff — into these pictures.” The new series was created over the past two years.

One painting, Abduction of Olaudah and His Sister, depicts figures in a forest—not heroically self-emancipating, but being kidnapped by an African man to be sold to Europeans. It is based on a 1789 account by Olaudah Equiano, who, after years of enslavement, played a key role in the British abolition movement.

Six for One shows a village celebrating after closing a deal — a half dozen human beings exchanged for a horse that sits stiff and wooden, like a Trojan gift.

A striking triptych — Outbound, Haul, and Cove — portrays Black figures in boats rowing to and from unseen European vessels offshore. In Outbound, a totem of figures — bound male captive, child, and sea gull — teeters precariously. In Haul, an ebony-skinned woman lounges atop a bag of cowrie shells, surrounded by luxury objects: an ornate clock, porcelain, an empty gilded picture frame, and a blond wig with a gold tiara.

The series also includes two portraits of Africa’s “white queens” — the European women who married independence leaders: Colette Hubert, who wed the first president of Senegal, Léopold Sédar Senghor; and Ruth Williams, wife of Botswana’s first president, Seretse Khama. These are rare non-Black figures in Marshall’s career, suggesting that African sovereignty from colonization was never as complete as often portrayed.

This series is quintessentially Marshall — a painter dedicated to depicting all facets of history without mythologizing or uplift. “I’m not a romanticist about anything — I’ve seen too much for fantasies about any kind of perfect Edenic past to be relevant to me,” he explained. “These paintings are not unique just because they’re about Africans, but because there’s complexity in the way we are being asked to think about and understand that history.” He added, “I am always trying to make the pictures that nobody else is making.”

Curator Mark Godfrey, in his opening remarks, called the works “complex” and predicted they “will be controversial.” Marshall disagreed, stating, “If you start thinking that they’ll be controversial ahead of time, then you’ve already shut off a part of your attention to what’s really going on in the work. I don’t understand why anybody would think these would be hard to digest or hard to encounter. The history is what it is.”

Artist, filmmaker, and cinematographer Arthur Jafa — a longtime interlocutor of Marshall — noted, “I always like to say that one of the superpowers of Black people is our ability to see the thing as it is, not as we wish it to be. Kerry knows this fundamentally.” The two met in their 20s, and Jafa brought Marshall in as a production designer for the 1991 film Daughters of the Dust, directed by Julie Dash.

Marshall’s career is marked by significant achievements. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955, he moved with his family to Los Angeles at age eight and later studied at the Otis College of Art and Design. He received a MacArthur “genius” grant in 1997, participated in the Venice Biennale in 2003 and 2015, and in 2016 set an auction record for a living African American artist when his painting Past Times sold for $21 million to Sean Combs. (This piece is included in “The Histories.”)

New York Times’ chief art critic Holland Cotter described Marshall as “one of the great history painters of our time.” The genre of history painting, once the most esteemed in European institutions, has long been Marshall’s ambition since a childhood visit to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art at age 10. This pursuit, alongside his commitment to figurative painting during the rise of conceptualism and new media art, often put him at odds with white peers and art critics in the 1980s and 1990s.

Marshall’s approach also diverged from the Black Arts Movement, which embraced African traditions and overt political messages. Instead, Marshall aimed to make paintings centering Black subjects that could stand alongside the best museum art, compelling viewers to look.

“If I’m going to be a self-styled, so-called history painter, then I want to do all … the things that history painters had always set themselves to do,” he said.

In the Royal Academy’s galleries, the subjects Marshall tackles include the Middle Passage; rebels, artists, and activists who fought for freedom; the Civil Rights Movement; American public housing history; the Black Power movement; and more. Yet, he approaches these topics obliquely and without sensationalizing suffering.

“In almost all the pictures I do, you have to reckon with the fact that the figures have agency,” he emphasized. “That’s a foundational principle that I work with.”

Marshall’s paintings result from a blend of meticulous historical research and creative imagination, often embedding anachronistic details as subtle “Easter eggs.” “My view of how history works is that it’s always part fact, part fiction, part fantasy,” he explained. “If you look through these paintings, there’s a little bit of the discrepancy between what could have been real and actual, and the way it could be imagined.”

He employs techniques such as layering imagery, incorporating a multiplicity of details, and the use of monochrome to demand sustained viewer attention. For instance, Black Painting (2003) is a subtle, tonal work depicting a bedroom scene just before the killing of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton in 1969.

The Africa Revisited series marks a departure from his earlier style. Rather than layered or dark compositions, these paintings are bright, vivid, and almost crystalline. “I’m distilling the image to what I think are the most necessary elements of the picture,” said Marshall. “I’m looking to not have any loose ends anywhere in there — not only loose ends relative to the subject matter, but loose ends relative to the construction of the space that they are occupying.”

Chicago-based artist Amanda Williams praised Marshall’s dedication: “Only Kerry can bring this conversation — this confrontation with our own past — to us Black diasporic people. I will receive it from him in a way I might resist it from others. I know he’s done his homework — he always has.”

Marshall’s The Histories exhibition serves as a vital, complex re-examination of history and identity — a compelling invitation to look unflinchingly at the past and its ongoing impact.