Art exhibitions and fashion shows share similarities, though some differences exist. Both serve as spaces of negotiation between a creative product and a prospective, often prosperous client.

In galleries, artworks—whether hung on walls, placed on the floor, suspended from the ceiling, or projected onto surfaces—rarely leave their fixed positions. Viewers move around them, drawing closer, shifting direction, and observing from different distances and angles as they choose.

In contrast, a fashion show places spectators comfortably on either side of the runway. The seating order reflects power, status, and wealth. Designers’ creations are carried by slender, elegant models who emerge from one end and return to the same point with measured strides, under blazing, flickering lights. These imaginative products are displayed on a luminous runway much like artworks are carefully lit in exhibitions. Yet amid the glitter, the designer’s couture—be it an evening gown or wedding dress—remains a silent entity, similar to a painting, sculpture, drawing, or photograph.

Both visual art and fashion design express aspects of human experience: skin, appearance, physical attributes, material needs, personal observations, cultural phenomena, inherited traditions, and responses to the natural and social environment. Crucially, both disciplines primarily deal with the body—the bare body—as seen in models posing in life-drawing classes. Artists across ages and cultures have depicted unclothed figures, from the earliest known stone figurine, the Venus of Willendorf (c. 28,000–25,000 BCE), to the present day. Similarly, the study of contour, color, measurement, posture, shape, and structure remains essential for fashion practitioners and students, who also base their concepts and designs on the naked human form.

Whatever labels they bear, creative individuals invariably infuse their work with elements of their personality—sometimes subtly, sometimes overtly, occasionally even aggressively. In some instances, these personal traits act as “the rope that leads the camel.” This is particularly true in societies that are compartmentalized and unreceptive to diversity in gender, ethnicity, class, or faith.

A pertinent example is Pakistan’s Zia era (1977–88), when the state suppressed political, social, and cultural views deemed unacceptable. In response, some artwork became essentially reactionary: once the dictatorship ended, its significance faded, leaving only historic value. Others, however, developed a language of resistance rather than mere reaction. No wonder their meaning, significance, and contribution have endured—a reality shared by those who feel marginalized in intolerant, patriarchal, and authoritarian communities.

The recently concluded exhibition by Fatima Faisal Qureshi and Fatima Butt, *The Weight of Elsewhere*, explored the relationship between the individual and society. Through Qureshi’s paintings and Butt’s drawings and mixed-media work, the duo disclosed emotions and memories, both recent and distant, alongside reflections on their socio-cultural surroundings.

Although the two artists share a studio and co-run an art gallery in Lahore, each pursues a distinct approach to developing content that is, to varying degrees, familiar and relatable.

Fatima Faisal Qureshi presented figures dressed, half-draped, and nude, depicted either alone or in company. Across her work runs a persistent sense of forlornness, depression, and temporality, hinting at separation. Each piece resembles a snapshot of human exchange—either just before or just after it has taken place.

An exception is the painting *Farewell My Lovers*, in which a party is shown in full swing. Even here, however, the central figure sits in quiet contemplation, one arm resting beneath her head, the other stretched across the sofa. The world Qureshi paints seems to exist beyond the reach of verbal discourse: one of comfort, longing, and inward gaze.

A number of actions can be discerned in these vigorously and sensuously layered canvases, all united by the realization of light. Some paintings glow with shades of yellow and green, others are heavy with blues, while a few are dominated by reds, crimsons, and mauves. Each, however, is a study of light and its alter ego, darkness.

The emphasis on artificial light in this series recalls Edward Hopper’s most celebrated canvas, *Nighthawks* (1942), where four figures are caught in the harsh glow of a city’s reflected lights—a scene of urban alienation at an hour when time feels immeasurable. In Qureshi’s paintings, too, the world exists in perpetual night.

Across cultures, the division of day and night has long been linked to ideas of good and evil. Phrases such as enlightenment (or *en-nightenment*, as Ngugi wa Thiong’o once proposed), dark ages, dark continent, dark soul, blackmail, bright white day, and purified self illustrate the value we attach to the two halves of the 24-hour cycle.

Night has often been imagined as the setting for crime or as the force prompting delinquency within individuals. Equally, the dark recesses of the unconscious are seen as the source of terrible acts we may neither recognize nor intend, and for which we later seek forgiveness.

Beyond forbidden pleasure, night is also the realm of dreams, a space where another chapter of personality unfolds. Unexpected, shocking, or shameful events occur while our eyes remain closed. Whatever we recall upon waking, regardless of the earthly hour, is consigned to night. Dreams, therefore, are shelved as a reality distinct from the routine one.

In this sense, Fatima Faisal Qureshi’s paintings are scenarios of a freedom not possible in the openness of society. Whether real, imagined, or a fusion of the two, they represent the lens through which the artist views the world and the self—or the self and the other—and how the self merges into another.

One example is *The Crisis of Love*, a subject familiar to the artist’s studio: painter, palette, brushes, and canvas on its easel. Yet here, every element is wrapped in ghostly shades of yellow-green, while the model reclines on a chair, legs outstretched. The scene is also reproduced on the unfinished canvas within the painting, creating a chain of images within images.

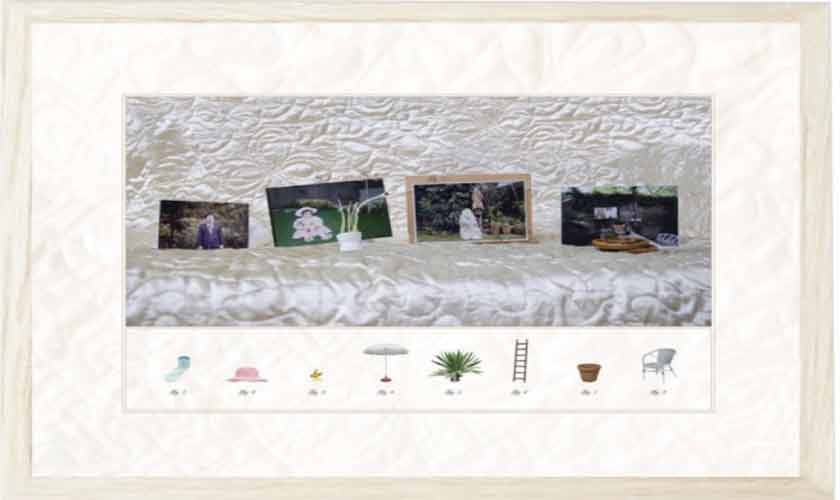

This layering of imagery finds an echo in Fatima Butt’s striking *Encyclopaedia Series*—four works each with its own subtitle: *The Garden*, *The Dining Room*, *The Living Room*, and *The Bedroom*. Butt’s photographic prints, mixed media, and ink drawings, shown in the two-person exhibition (August 29–September 12, Kaleido Kontemporary, Lahore), summon childhood memories from a specific period.

These years are recalled through objects no longer in everyday use and preserved only for their archival value. In each work, Butt arranges groups of small photographs—fragments of the past—in sequence, linking family members’ interactions with their possessions. A key beneath each piece connects each cut-out object to its place in the original family photograph of the artist’s parents and siblings.

In these works, the photographs are arranged on a quilted sheet draped over furniture, often accompanied by other decorative items. The artist captures intimate family recollections—a practice familiar across South Asia. The reminder is clear: it is not the material, condition, or cost of these small objects that matters, but the intimacy, fear, loss, and desire attached to them. They express their time, and it is these associations that hold a family together.

As Tolstoy observed at the opening of *Anna Karenina*: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/1344869-being-and-other-objects