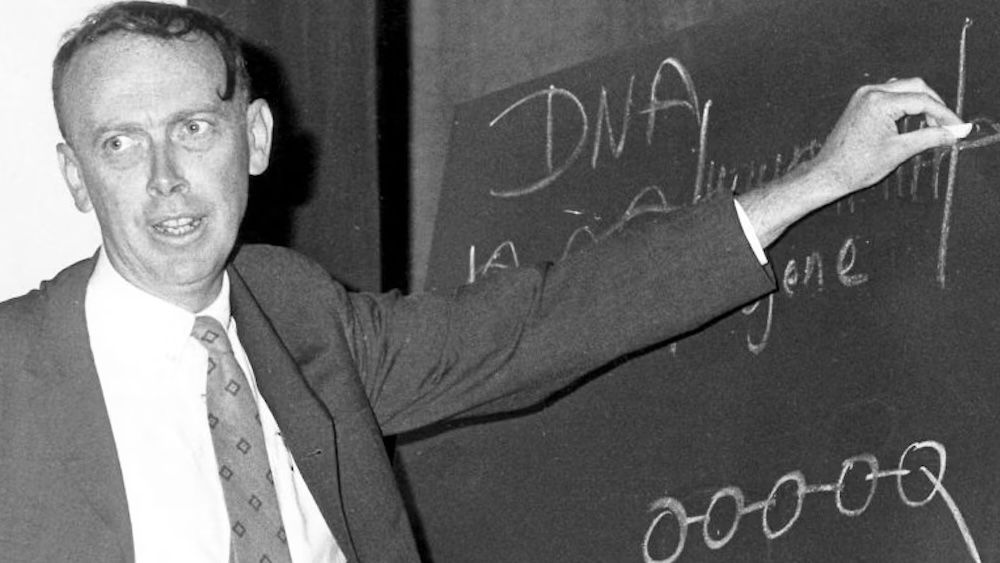

**James Dewey Watson: Pioneering Molecular Biologist and Controversial Figure**

James Dewey Watson was an American molecular biologist best known for co-winning the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering the structure of DNA and its significance in transferring information within living systems. The importance of this discovery cannot be overstated. It unlocked the understanding of how genes work and gave birth to the fields of molecular biology and evolutionary phylogenetics. This groundbreaking achievement inspired and influenced my own career as a scientist and as director of a bioinformatics and functional genomics research center.

Watson was also an outspoken and controversial figure who transformed the way science was communicated. He was the first high-profile Nobel laureate to offer the general public a shockingly personal and unfiltered glimpse into the cutthroat and competitive world of scientific research. Watson died on November 6, 2025, at the age of 97.

—

### Watson’s Pursuit of the Gene

Watson attended the University of Chicago at the young age of 15, initially intending to become an ornithologist. However, after reading Erwin Schrödinger’s book of collected public lectures on the chemistry and physics of cellular operations, *What is Life?*, he became captivated by the question of what genes are made of — the biggest question in biology at the time.

At that point, chromosomes were known to be a mixture of protein and DNA and were understood as the molecules of heredity. Most scientists believed proteins, with their 20 different building blocks, were the likely carriers of genetic information, as opposed to DNA, which comprises only four building blocks. The 1944 Avery-MacLeod-McCarty experiment, however, demonstrated that DNA was indeed the carrier of inheritance, shifting scientific focus immediately toward understanding DNA.

Watson completed his doctorate in zoology at Indiana University in 1950, followed by a year in Copenhagen studying viruses. In 1951, he met biophysicist Maurice Wilkins at a conference. During Wilkins’ talk on the molecular structure of DNA, Watson saw preliminary X-ray photographs of DNA, which inspired him to join Wilkins at the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge to pursue the structure of DNA.

At Cambridge, Watson met physicist-turned-biologist Francis Crick, and the two quickly bonded over their shared research interests. Together, Watson and Crick published their seminal findings on the DNA structure in the journal *Nature* in 1953.

—

### The Discovery and Recognition

The same issue of *Nature* also featured two other papers on DNA’s structure — one co-authored by Wilkins, and another by chemist and X-ray crystallographer Rosalind Franklin. Franklin’s X-ray photographs of DNA crystals contained the crucial data needed to solve DNA’s structure.

The combined efforts of Franklin and the Cavendish Laboratory team led to Watson, Crick, and Wilkins receiving the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

—

### The Prize and the Controversy

Despite their awareness that Franklin’s vital X-ray photographs had circulated within the internal Cavendish Laboratory report, neither Watson nor Crick acknowledged her contributions in their famous 1953 *Nature* paper. In 1968, Watson published a book recounting the discovery’s events as he experienced them, wherein he minimized Franklin’s contributions and referred to her with sexist language.

Although the book’s epilogue did acknowledge Franklin’s contribution, it stopped short of giving her full credit. Some historians argue that Franklin’s work was not formally recognized partly because it had not been published at the time and was considered “common knowledge” within the laboratory, where researchers often shared data openly.

However, the unpermitted use of Franklin’s data and failure to attribute her has become widely regarded as a glaring example of poor scientific ethics and the mistreatment of female colleagues by male counterparts.

Since the Nobel Prize was awarded, many have reframed Rosalind Franklin as a feminist icon. Whether she would have embraced this is unclear, especially given the painful omission from the Nobel Prize and disparaging remarks in Watson’s narrative. Nonetheless, her contribution is now universally recognized as critical and essential — and she is widely regarded as an equal contributor to the discovery of DNA’s structure.

—

### The Future of Scientific Collaboration

How have attitudes and behaviors toward junior colleagues and collaborators evolved since Watson and Crick’s Nobel Prize recognition?

Today, many universities, research institutions, funding agencies, and peer-reviewed journals have implemented formal policies designed to transparently identify and credit the work of all researchers involved in a project. While these policies are not perfect, the scientific environment has become more inclusive and fair.

This evolution partly reflects the recognition that rare is the scientist who can tackle complex problems alone. Moreover, there are now clearer mechanisms and frameworks for resolving disputes — guidelines found in journal author policies, professional association codes, and institutional regulations.

For instance, *Accountability in Research* is a dedicated journal that critically analyzes practices promoting integrity in scientific research. Guidance on structuring author attribution and accountability marks important progress toward ethical fairness in science.

—

### Personal Reflections on Collaboration and Ethics

Throughout my own career, I have experienced both positive and negative instances concerning authorship and credit. These range from being included on papers as an undergraduate to being excluded from grants or removed from authorship lists without notification.

Most of my negative experiences occurred early in my career, likely because some senior collaborators felt they could act without accountability. Thankfully, these situations are less common now, as I am upfront and explicit about my expectations for co-authorship from the outset of any collaboration.

I suspect my experiences mirror those of others and are even more pronounced for individuals from groups underrepresented in science. Unfortunately, inappropriate behaviors — including sexual harassment — persist within the field. It is evident that scientific communities, much like society at large, still have considerable progress to make.

—

### Watson’s Later Career and Legacy

After co-discovering DNA’s structure, James Watson went on to study viruses at Harvard University and later led Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, during which he revitalized and expanded its physical space, personnel, and global reputation.

When the Human Genome Project began, Watson was a natural leader to drive it forward. He eventually stepped aside after a protracted debate over whether the human genome and genes themselves could be patented. Watson was firmly opposed to gene patenting.

Despite these remarkable contributions, Watson’s legacy is complicated by his long history of racist and sexist public remarks and his ongoing disparagement of Rosalind Franklin, both personally and professionally. Furthermore, it is regrettable that he and Crick chose not to recognize all contributors at crucial moments in the discovery of DNA’s structure.

—

James Dewey Watson’s life and work reflect both the transformative power of scientific discovery and the ongoing challenges within scientific culture. Recognizing the past, learning from its mistakes, and striving for honesty, inclusion, and fairness are critical as science moves forward.

https://www.livescience.com/health/genetics/james-watson-controversial-co-discoverer-of-dnas-structure-dies-at-97