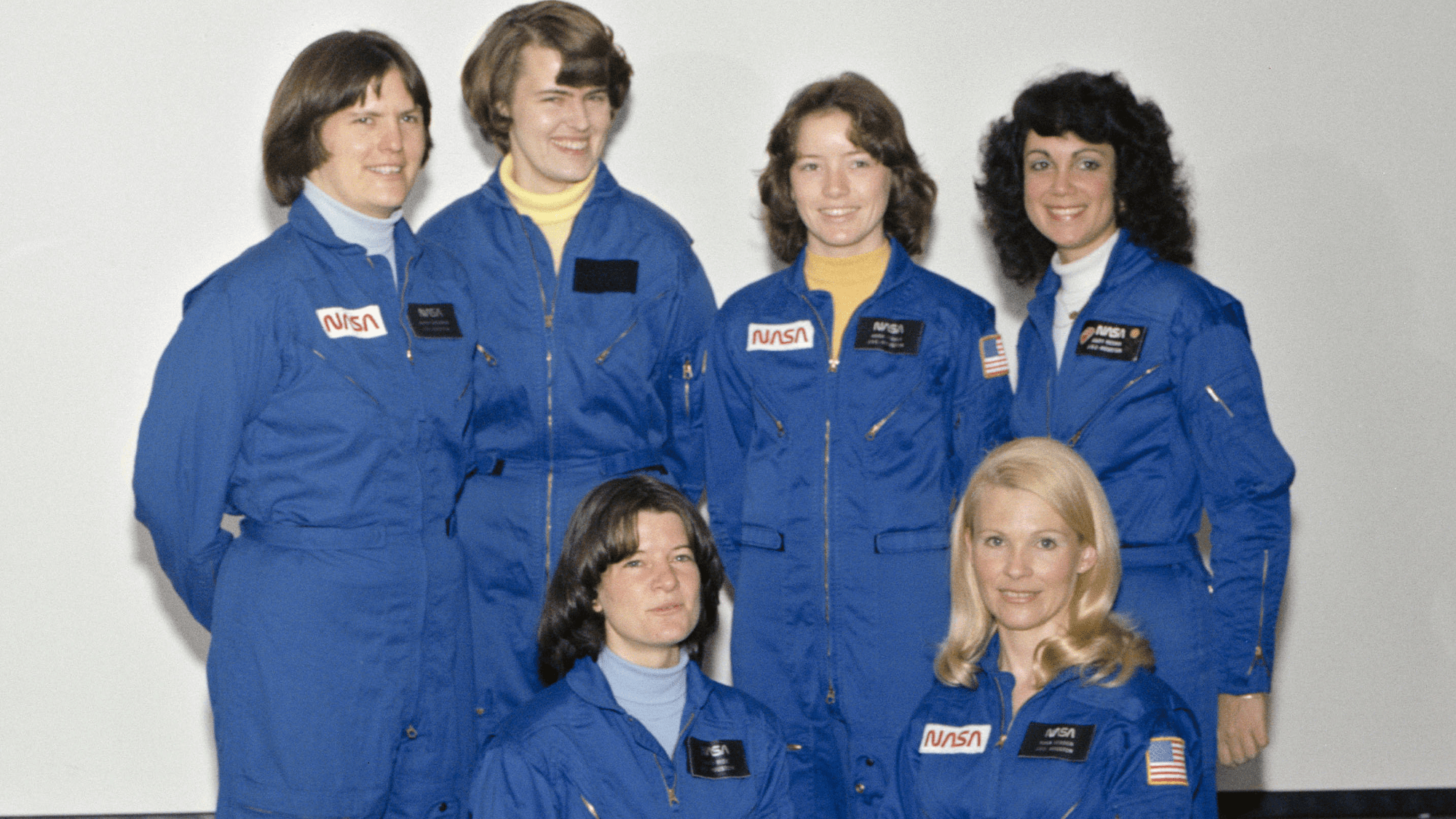

Get the Popular Science daily newsletter💡 Breakthroughs, discoveries, and DIY tips sent every weekday. Email address Thank you! Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. Excerpted from On a Mission: The Smithsonian History of US Women Astronauts by Valerie Neal. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Smithsonian Books. Out October 28 and available wherever books are sold. The Trailblazing Generation: Astronauts for Space Shuttle Missions, 1978-1990 After nearly five years of planning, recruiting, evaluating, and interviewing applicants, NASA announced the selection of new astronaut candidates at a press conference in Washington, DC, in January 1978. Members of the media peppered administrator Robert Frosch with questions and sought assurances about the selection process, the number of women and people of color, and the number of military and civilian pilots selected. Chris Kraft, director of the Johnson Space Center, fielded questions and explained the experience-based filters and rating process for competitive selection. He was satisfied that the men and women selected “represent the most competent, talented, and experienced people available to us today.” The main press conference to introduce the new astronaut candidates to the public occurred on January 31. The selectees convened at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston to meet one another and the press. The NASA auditorium was filled to capacity with reporters, camera crews, VIPs, veteran astronauts, and anyone else who could squeeze in to see them for the first time. After opening remarks Kraft called the thirty-five men and women to the stage. NASA had chosen fifteen pilots and twenty mission specialists. Six of the mission specialists were white women: Anna Fisher, Shannon Lucid, Judith Resnik, Sally Ride, Rhea Seddon, and Kathryn Sullivan. Fisher and Seddon were medical doctors; the other four held PhDs in different fields. The two youngest, Ride and Sullivan at age twenty-six, had just completed graduate school; this would be their first professional job. Lucid, the eldest at thirty-five, and the other three were a few years into research and medical careers. The group also included three African American men (one of them a pilot) and an Asian American man. Of the total, twenty-one were military officers and fourteen were civilians. After training, they would join the twenty-seven older men in the active-duty astronaut corps and double the size of the corps to sixty-two astronauts. The new position of mission specialist made it possible for women and minorities to become astronauts as scientists and engineers without having to be high-performance jet pilots, the main reason the first recruitment to diversify the astronaut corps succeeded. After the introductions and applause, the formal program ended, and media representatives were invited to meet the astronauts-to-be for interviews. As Kathy Sullivan remembered it, most of the media flocked to the women and the minority men-the “ten interesting ones”-as the big news story. The “standard white guys” were able to depart quickly, while media kept the other newcomers engaged for hours. Most of the astronaut candidates had never been exposed to such a media gaggle and were either bemused or exhausted by the experience. Sullivan recalled with gratitude the helpful role played by the only woman who had served on the Astronaut Selection Board, Carolyn Huntoon, and another prominent NASA woman, engineer Ivy Hooks. They advised the women not to worry about their wardrobe or hairdo but to focus on what they did and did not want to say for publication. Their conversations with the media would make a greater impression than their appearance. As the media started to create a sort of composite persona to explain to the public who the women astronauts were, they questioned the women about both their common and distinctive traits. Huntoon basically advised them to be smart, confident, and poised, and cautioned that they take some care in what they revealed. Journalists could not glean by observation alone that two of the women were medical doctors, three scientists, one an electrical engineer, one a newlywed, two divorced, one a married mother of three, one a classical pianist, another a tennis champion, one drove a Corvette, another owned her own airplane, and one was Jewish. Those were the kinds of personal details that reporters were eager to discover. A lot rested on how the first six women fielded such questions. They needed to be mindful of their privacy as they moved into new public roles and stay alert to comments that might stereotype them. Between interviews, the six spontaneously convened in the ladies’ restroom to compare notes on questions and answers and start considering potential boundaries. Twenty-five years later, NASA historian Jennifer Ross-Nazzal surveyed the resultant media coverage from that day and the next few years as the women completed training and began to fly in space. Many articles, she noted, reported on their physical features, size, weight, and marital status. Such information was rarely included in stories about male astronauts. Women’s magazines took a great interest in their fashion choices, style, beauty tips, hobbies, homes, and domestic pursuits. The petite women garnered more attention than the larger-framed “robust” ones, although all were specimens of good health and fitness, evidence that some media attention was biased toward the stereotypically feminine type of woman rather than the athletic or tomboy type. The total group of astronaut candidates selected into the 1978 class called themselves the Thirty-Five New Guys (TFNG), a sanitized variant of the military phrase, “the F’ing New Guys.” They outnumbered the twenty-seven members of the astronaut corps held over from the 1960s, many of whom had not yet flown and were skeptical of the newcomers, especially the civilian scientists and engineers who had no military flying experience. With a larger astronaut corps, the “old guys” feared losing their opportunities after waiting more than a decade to fly and initially kept their distance. They had a grace period of two years while the TFNG went through their core training and evaluation, and they had been promised the first shuttle flights. But the new candidates proved so adept in training that they completed it in one year while the first shuttle launch schedule slipped from 1979 to 1981. Those changes left ample room for the “old guys” to feel uneasy. They carried forward the astronaut culture of the 1960s and early 1970s, in which military pilots reigned over second-class civilians and scientists. Officially Group 8 in the history of astronaut selections, the TFNG class acquitted themselves well. They vindicated the capability and value of mission specialists and eased the acceptance of women and minorities in future classes by deflating concerns about sex and race. They gradually won the respect of the veteran astronauts. The women and the men of color in the class became instant role models for young people and symbols of achievement for everyone. By the year 2000, members of this class had completed their flights in space, five of them-including Shannon Lucid-having flown five times each. Altogether they served on fifty shuttle mission crews and cumulatively logged almost a thousand days in space, demonstrating everything the space shuttle was designed to do-an illustrious record for the first class of shuttle-era astronauts. After selecting the 1978 group of astronauts, NASA held additional recruitments at approximately two-year intervals to increase the size of the astronaut corps. During the period of 1978 through 1990, fourteen more women were selected to be astronauts. These first twenty, plus a few of the other women chosen after 1990, were part of the post- World War II baby boom. Most of the women selected by 1990 were midcentury girls, all born within a few years on either side of 1950, most of them starting school in the relatively placid 1950s and coming of age in the social and cultural milieu of the tumultuous 1960s. If they were old enough to notice, the signal events of their youth included the beginning of the space age with the launches of Sputnik, Yuri Gagarin, Alan Shepard, John Glenn, and Valentina Tereshkova in the period between 1958-1963. All were old enough to witness on television Neil Armstrong’s and Buzz Aldrin’s landing on the Moon in 1969. For some, the space age spelled their destiny; they cite one or more of those early missions as the pivotal event in shaping their aspirations. These women generally were products of middle-class families, white neighborhoods, and public schools. As noticeably intelligent students who flourished in academics, they also spent their youth in such normal pursuits as Girl Scouts, sports, music and dance lessons, and school activities. Rock and roll and folk music were the sound tracks of their youth. Star Trek debuted on television in 1966 while they were teenagers. They might have seen 2001: A Space Odyssey when it was released in 1968 and watched family-oriented shows on television and at the movies. For young girls in the 1950s and 1960s, there were not many serious role models in popular culture, where the standard for celebrity was beauty, or in public life, where notable women were rare. Instead, they looked for encouragement and support from their parents and teachers, both men and women-people in their personal lives rather than the public sphere. Although some encountered active academic bias against studying physics, engineering, and medicine, most were able to find an open-minded mentor whose guidance primed them for success. The deciding factor, they said, was proving their determination and capability. Once that was established, lab positions, research projects, funding, awards, and jobs tended to follow. Unsurprisingly, the aspiring scientists and engineers who faced early resistance often graduated with honors. Their tenacity was a harbinger of success. Despite their achievements, the astronauts had faced discrimination in the world outside of NASA. Rhea Seddon recounted that she was not allowed to take out a loan for the condo she was buying in Texas, despite being a medical doctor with three years of experience and a newly named astronaut; at the age of thirty, she had to ask her father to cosign the loan to guarantee that he would pay the mortgage. She had already experienced barriers as the only woman surgical intern when she was denied access to the doctors’ lounge in the hospital and had to take her breaks in the nurses’ restroom between surgeries. Anna Fisher applied for a surgical residency only to be told by the department chair that women didn’t belong in surgery, so she went into emergency medicine instead. The young women who became scientists, engineers, medical doctors, and astronauts shared a commitment to graduate school in preparation for a career. In an era when educated women who worked were mostly confined to teaching or nursing, and those without bachelor’s degrees or licenses were secretaries, clerks, or retail workers, these women were determined to chart different paths for themselves. Some were the first in their families to attend college. They headed into graduate school in the late 1960s and early 1970s on the cusp of major changes in the educational and social environment. They confidently pushed forward on their journeys to become scientists, engineers, and physicians. They were often the first or only woman-or one of very few-in their advanced science, math, and engineering courses at both the undergraduate and graduate levels, and in medical school. Some were the first women ever granted a degree in a particular field at their university. As they moved onto a career path, they were often the first or only woman in a medical residency or a corporate office or at a field site. Most were aware that they could not fail, for that would only reinforce bias and make it harder for the next woman. Shannon Lucid probably had the hardest time launching her career. She was a few years older than the other women astronauts, just enough so that she was truly an anomaly as a female chemist and biochemist at the University of Oklahoma. She spent ten frustrating years being rejected for positions for which she was fully capable and working through a series of assistantships before finally breaking through to what she considered a real adult job. Among the trailblazing women, those who had long aspired to spaceflight learned to fly airplanes in hopes of improving their chance to become an astronaut, and it was not uncommon for them to come to NASA with a pilot’s license in hand. Lucid, passionate about flying since childhood, held multiple flight ratings and owned her own plane; she could have become a commercial pilot. Similarly, Marsha Ivins started flying at age fifteen to prepare to become an engineer and astronaut, Mary Cleave earned her pilot’s license at age seventeen and hoped to fly jets at NASA, and Rhea Seddon took flying lessons after graduating from medical school, a gift from her father to celebrate her success and a conscious decision to improve her prospects whenever NASA decided to hire women as astronauts. More than half of the first women to become astronauts took flying lessons or earned pilot’s licenses, although they were not required to do so. Some of the women in this generation believed that eventually women would be astronauts. Others never aspired to be astronauts because it seemed impossible; they saw only a male space agency and male astronauts when they were young. Their interest sparked when they learned of NASA’s intention to recruit and select women, and not until they applied and interviewed did they realize how much they truly wanted it. Sally Ride read NASA’s announcement in the Stanford University student newspaper. Had she not picked up that particular issue on that particular day, she might never have known or applied. Kathy Sullivan’s brother, a professional pilot, was applying and challenged her to apply, too. A budding oceanographer bent on exploring the seafloor, she didn’t take him seriously until she read the announcement and realized that exploration in sea and space had much in common. Rhea Seddon, Anna Fisher, and several others were encouraged by professors or coworkers to apply, people who saw their potential before they themselves recognized it. This first wave of twenty women astronauts selected through 1990 proved more than capable in training and in flight. They carried out every orbital task such as tending to spacecraft systems, science experiments, spacewalking, robotic operations, and more- all except actually flying the shuttle because there were no qualified female military test pilots in the early selection rounds. Eileen Collins broke through that barrier when she was selected into the 1990 astronaut class. Each woman has a compelling origin story arising from or intersecting with other American stories and themes. They have become admired role models and influenced the paths of younger women who have joined the space program as astronauts and in many other roles. Almost all women astronauts have been first at something, usually without aiming to be, as their individual stories reveal. But, to paraphrase Judy Resnik, Kathy Sullivan, and others, being first isn’t the point. If something is worth doing, it doesn’t matter whether one is the first, fifth, or one hundredth. It is the doing that counts. The Class of 1978 NASA received 8, 079 applications during the first recruitment for space shuttle astronauts, 1, 142 of which came from women. Through the winnowing process, 208 applicants (21 of them women, including Carolyn Griner and Mary Helen Johnston from the 1974 Spacelab simulation at Marshall Space Flight Center) were invited for a week of interviews and physical evaluations at the Johnson Space Center. In the end, NASA selected six impressively qualified women. These first six found NASA partially ready for them, welcoming them into the “NASA family.” But not everything was fully prepared. For example, the astronauts’ gym did not have a women’s locker room or even a women’s restroom, and no one thought to remodel it until after the women arrived. NASA issued workout clothes to the astronauts, including athletic supports for the men, but no one thought of sports bras for the women. Airfields where the astronauts flew while in T-38 training had locker rooms and restrooms only for men. Some NASA “old-timers” kept an eye on what the women wore to work and protested if their attire was “too casual,” despite the men forgoing ties or wearing jeans. Carolyn Huntoon fielded some of these complaints by pointing out that there was no dress code for men, so why should there be one for women? Such issues gradually resolved as the workforce came to terms with treating women equally. This first group of women wanted to blend in, to be one of the guys and not call attention to themselves as women. Anna Fisher noted, “It never occurred to any of us to ask for special accommodations for anything.” Sally Ride and Anna Fisher shopped for khaki pants and polo shirts to match the men’s office attire. Some wore little or no makeup to work. The women had fun together with the men playing in the employee volleyball and softball leagues, running and working out, competing in the annual chili cook-off, going to happy hours, and socializing with spouses and families. All of this was consistent with their desire then (and still) to be regarded as astronauts, not women astronauts, and not a separate subset of the astronaut corps. They knew, however, where there was resistance or bias to overcome. Some of the older male astronauts initially had trouble accepting women and scientists into their ranks. So, too, did some of their classmates. Although the TFNG generally bonded and mutually supported one another, it didn’t happen immediately. One of the men in the 1978 class, Mike Mullane, was honest enough to admit his initial doubts about women and scientists who hadn’t been tested and seasoned the way military pilots had been. “I felt a subtle hostility toward the civilian candidates .[they] hadn’t paid their dues,” he confessed. “I was in another galaxy when it came to working with women. I saw women only as sex objects . We were flying blind when it came to working with professional women.” The military men had never worked with women as peers; they related to women as secretaries, girlfriends or wives, or family members. For some, it was a difficult transition to become more open-minded and tolerant of those who were not the stereotypical military fighter pilots. The most senior woman at JSC at the time led the way in bringing women into the astronaut corps and addressing problems that arose. Carolyn Huntoon, who managed the research labs in the biomedical division and had been studying astronaut health since the Apollo era, was the only woman on the selection panel that conducted interviews for the 1978 class (and all the subsequent astronaut classes until she became JSC director in 1994). She was a strong and respected advocate for scientific and technical women in the space program and was herself a prominent scientist in her field of human physiology. She took the women astronaut candidates under her wing as an informal den mother for advice and counsel. She became their hero. Some still remember her advice to always use good judgment, which helped them navigate whatever circumstances they found themselves in. Huntoon observed that as the shuttle era began, NASA didn’t discriminate, but individuals did. Some gave women a hard time, and some simply couldn’t get over the fact that women are not exactly like men. She had to explain that doing something differently doesn’t mean one isn’t up for the job, or that not acting like “one of the guys” wasn’t a problem. She thought that the biggest challenge during these first years was to change attitudes, and she used her influence for that purpose. The trailblazing generation of women astronauts found a welcoming environment at JSC and believed that NASA had committed to their success. Despite occasional hiccups, they felt equally supported by their trainers, flight surgeons, and other personnel. They have described the Astronaut Office as both a cooperative and competitive workplace. For some time, though, they sensed a not-so-subtle hierarchy that determined who could be a leader and who would be assigned to flights. At a macro level, the office sorted into pilots and mission specialists. Within that scheme, the hierarchy was finer grained. Military pilots were at the top, with more numerous Navy pilots outranking Air Force pilots. Civilian pilots ranked below military pilots. Next down the ladder were mission specialists, with military again ranked above civilian, and women ranked below men. This wasn’t explicit or codified in writing; rather, it was deduced from the types of assignments one received and how long one waited for a mission assignment. Another sign that all was not perfectly equitable was a sexist joke that circulated within the 1978 class, but not to everyone. The hand-drawn flowchart parodied astronaut selection criteria for women. Among the qualifications shown were IQ, academic degree, breast size, weight-to-height ratio, and stance on the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). The only path for a woman to qualify as astronaut material according to this chart was to be a US citizen, not a genius, have a PhD degree, be slim, have a thirty-eight-inch or larger bust, and be against the ERA. On the chart, pilot candidates had a straight path to selection simply by meeting all advertised requirements, and male mission specialists could breeze through despite meeting no requirements at all. Most were in their late twenties and early thirties and not yet married. Over time, in fact, several astronaut couples paired up or married. At the beginning, though, women sometimes felt that some of the men acted like fraternity brothers, sizing them up as dating material rather than coworkers. Some weren’t comfortable with sexual banter, raunchy jokes, and quips about who was sleeping with whom. The six women settled into training and then work assignments, proving their abilities and dedication. Seddon recalled that the women knew they were being watched for any signs of weakness, and no one wanted to “look like a wimp.” Yet some tasks and equipment were sized for larger, heavier bodies, which made it hard for smaller women to perform well. In her case, it was the parachute size used in survival training. It was so large and she was so lightweight that she kept ascending when she was supposed to descend. Veteran Apollo astronaut Alan Bean, training supervisor for the TFNG class, reported that the women performed very well. “I always thought we were letting women do what was instinctively a man’s job. I don’t think that anymore,” he said. The women, however, were not intimidated or discouraged, and they called out what they saw as misguided and inappropriate. The same male astronaut who admitted that he didn’t know how to deal with women professionally said that he quickly learned to be careful about what he said and how he acted because a woman astronaut would give him an icy stare or insult him right back. Perhaps speaking for all of them, Seddon remarked, “We really were blazing a trail in defining what we could do in this world, what we were willing to do, and what we wanted to do.” One of Sally Ride’s T-shirts said it all: “Women’s Place is Now in Space.” Valerie Neal is a curator emerita in the Department of Space History at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, where she oversaw the human spaceflight collections from the space shuttle and International Space Station programs, and she initiated the collection of artifacts from women astronauts. Her previous books include Discovery: Champion of the Space Shuttle Fleet and Spaceflight in the Shuttle Era and Beyond.

https://www.popsci.com/science/nasas-trailblazing-generation/

NASA’s trailblazing generation